“We are all born into someone else’s story,” a dear teacher and friend, Jeanne Boydston, once said to me. The line still strikes me as true, as clear-headed a look at existence as looks come near and most worthy of the woman who uttered it with a wry grin and a gentle nod of her head to the fates. Jeanne was not quite of my parents’ generation nor of mine, a woman between but from far enough south that she could speak such truths un-dainty, un-gussied up, un-dodged.

That one true sentence has come often to mind as I sort through old family photos, preparing them for my descendants in the ways proper of elders. There are plenty of pictures of me as a small child—moving pictures and still—but I’ve not yet found a single one of my mother and me.

That one true sentence has come often to mind as I sort through old family photos, preparing them for my descendants in the ways proper of elders. There are plenty of pictures of me as a small child—moving pictures and still—but I’ve not yet found a single one of my mother and me.

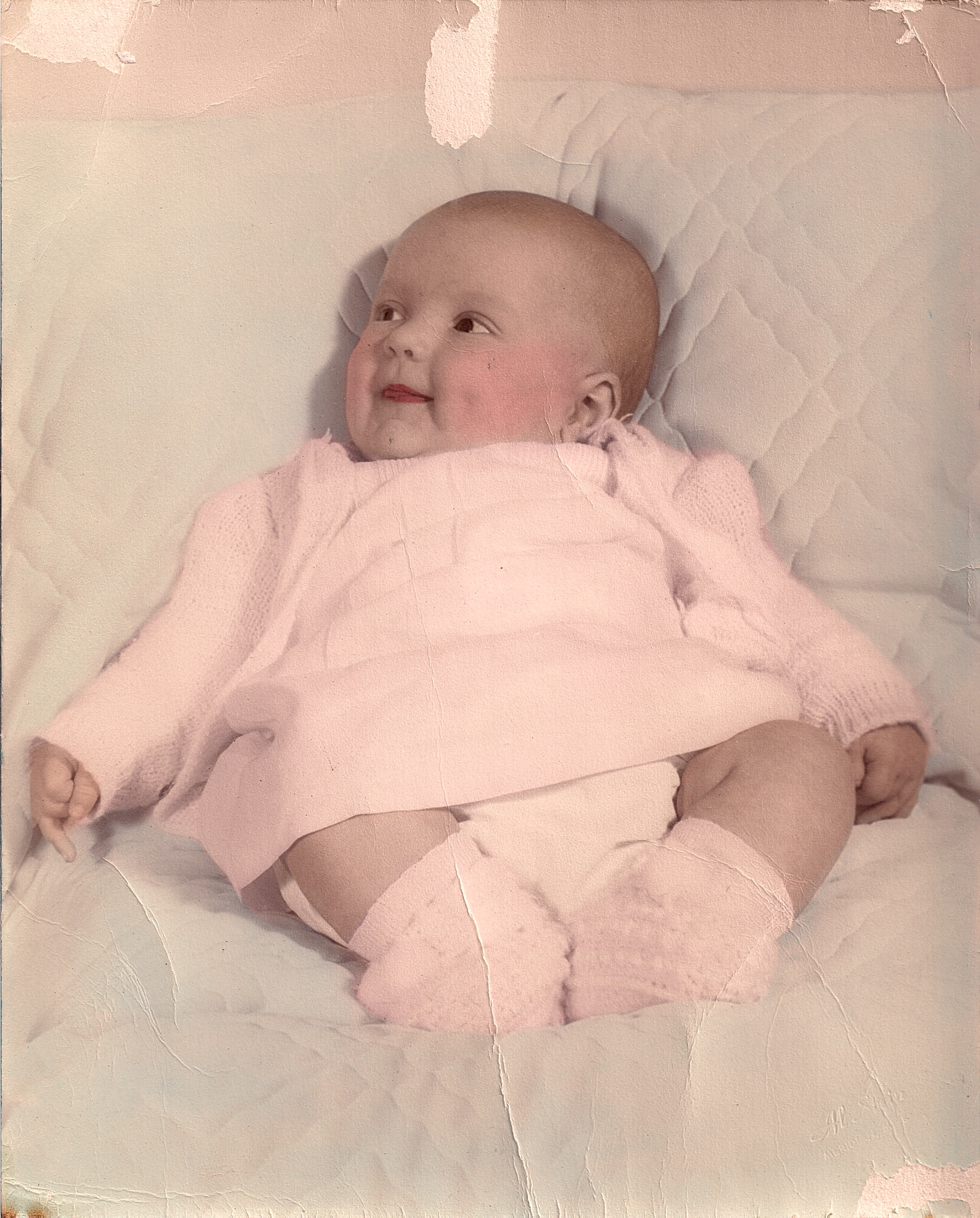

She was always the gorgeous one behind the camera, dressing us, fixing our hair just so, telling us to smile and stop fidgeting, recording family for all times, ensuring that the photos were taken, developed, colorized if needed. “Well, the world is in color,” she responded to my long-ago query about why this baby photo was drenched in pale pinks and blues when the original (which we also had) was clearly black and white. “If the world is in color, you should be, too. So I paid extra to have it done.” Period. That was it. I went on with living and didn’t think consciously about that again until last night.

All along I knew I broke into my mother’s dreams for her life by being born a girl or at all, for when I showed up she still knew she was beautiful and she worked in a bank and had nice clothes and a new car and greatly enjoyed all that until she was pressured to leave it by the church that she joined when I was four, and so I began writing early and solely for myself, to keep my own record of the stories she and the other adults were telling, to make sure the story of my life wouldn’t get written by people who wanted the rough edges smoothed and the hard times forgotten whole cloth. Writing was an issue from the week I turned five and pencilled into the margins of my Bible a short letter to God in a church service. From that week forward, Mama and I were at open odds. Not always, but often.

All along I knew I broke into my mother’s dreams for her life by being born a girl or at all, for when I showed up she still knew she was beautiful and she worked in a bank and had nice clothes and a new car and greatly enjoyed all that until she was pressured to leave it by the church that she joined when I was four, and so I began writing early and solely for myself, to keep my own record of the stories she and the other adults were telling, to make sure the story of my life wouldn’t get written by people who wanted the rough edges smoothed and the hard times forgotten whole cloth. Writing was an issue from the week I turned five and pencilled into the margins of my Bible a short letter to God in a church service. From that week forward, Mama and I were at open odds. Not always, but often.

So when writing became my life’s work, Mama disapproved. By then I had a good twenty years in of trying unsuccessfully to beat our odds—of doing something of which she would approve, of bringing her some of the joy she brought me. Writing, it seemed, especially when I got an award and recognition and then eventually a book contract, would surely do that, no? Oh no. There was no chance while Mama was alive to write for her. Even the goodnesses, the color-drenched memories of childhood, the signal events of us being well in the world, our triumphs, brought her no comfort. She only ever read one story all the way through (1st grade) and then never again: my writing would stray from her story, she knew, and that was too much. How, why would I say such things for strangers? Who were they, to deserve to know such things? She was right in so many ways, for some people do in fact ridicule and demean writers for whatever we offer, some humans believe themselves better than others who have struggled and dared to speak of it, some people don’t want their real deeds mentioned out loud or at all, and others simply don’t like to read. So be. I wrote on anyway, for writing is truth and beauty and death-kissed breath to me. Without it, I do not exist.

But when the last thing I shared with my mother, my first published book (Point Last Seen, 1997), got me disowned in the first few pages for two years straight, I decided to carry on alone and never to speak of it again with her. In Mama’s world, you could always fix the pain of any story by telling it differently, by cleaning it up, by skipping straight over the ruts that tripped you up so badly you skinned your nose on somebody else’s blacktop path. She was more kin to many other people about us than to me in this instance. I have a mortal dread that silence will fuse the asphalt to my face, to my bones, and everybody knows you can’t see jack siccum through hot tar and rocks anyway. I wanted to write through my scars well enough to reach through her pain and say to this woman who never stopped being the beautiful center of our family, “See, you did do so much good, Mama. See how well we all turned out? You paid the price of your raising, extra by all accounts and silences, and we got the benefit of that.”

Homely as ever, with none of her physical grace and little of her fire, I hid my writing away, kept silent about it, but took to saying these things to her when I could, trying to navigate through the boulders between us, but she did not want comfort from me. I saw her take it from her church family, and for this I was both glad for her and achingly sad for the two of us, permanently estranged despite our unbreakable bonds of love and stories untold.

Now that Mama’s walked on from us and I can think of her without weeping every time, many of my writings turn her direction no matter where they started, and I am unsure why, but I suspect it has something to do with the powerful lightness of being that came with me being born into her story. For all time, I will be her first daughter, the perennial heathen, the one who would not toe the line. The one who determined that since our stories—all of them, every line—are writ in full living color, then any telling anew of them must pay extra to do the same. This I learned from my mother.