There are those among us now who, fired up with self-righteousness and anger, believe they know best how to legislate women’s bodies and the miracle that is human birth. Corporations have weighed into the fray, as has the Supreme Court once again, and the rancor of those who would control this for others is spectacular, ugly, and far-reaching. Some want to ban contraceptives, others to make miscarriages an “investigational event.” Let’s be real clear: they want judges and the police and the government (federal, state, local, church) to control women’s bodies on a daily basis.

If that in itself weren’t demeaning enough, they want this control through the times that are the most personal, intimate, and gut-wrenching.

I am no longer of child-bearing age (thank god and a skilled surgeon), but when I was I needed contraceptives, and I had one miscarriage that broke my heart in so many pieces it won’t ever come back together again. What these power-mongers do not understand about either issue is everything that counts.

My husband and I were startled and pleased to learn I was carrying his child a few years ago. We had not expected such a grace; it came anyway. Immediately we began overhauling our lives and home to welcome this child, Joah. Sharing pregnancy with a person who loved me and the baby was a first: at last I would find out what it would be like to not be battered while carrying a child. I would finally get a chance to be a mother unassailed: what a gift, to have a loving partner share it all! I’d do it well, I vowed, and never you mind that some members of my kin were horrified that at our age we would have a child: had they any legislative ability, Joah would’ve been denied his boarding ticket posthaste: instead, those folks had their angry say and disappeared from our lives, and I watched them leave with sadness leavened by the promise of a family member who was about to show up to stay—at least for the next 18 years! Medical practitioners, too, we quickly learned, are geared now to help younger people procreate and seemed oddly disconnected from us. Birth has been so medicalized since I had two children via natural (Lamaze) methods thirty years ago that I barely recognized any of it. No matter. I went through my days wrapped in the grace of this child, speaking and singing to him, moving through this world not as one, but two.

Until the day all went still within me. And then the next day the bleeding started, at the wrong time, only a little over three months along. We rushed to the designated emergency room on a slow Sunday afternoon, expecting help, but finding instead exceptionally callous doctors and nurses who merrily stood in the halls outside my room joking and laughing about parties and the such while Stewart and I faced the death of our child in the most viscerally demeaning ways I can imagine. Listening to the laughter of the staff on the other side of the closed door, we had to rifle frantically through the cupboards trying to find a blue plastic sheet when the first one was soaked through. Huge clots the size of my fists were coming, and Stewart helped me into the attached bathroom and then went to try to get the nurse to come in and find a blue sheet. (The nurse was in mid-story about something that had taken place that weekend in town and couldn’t be bothered, so Stewart rifled through the cupboards in another ER cell and brought a stack in to me.)

I am a grown woman. I have faced down a slew of outright terrors by myself and done a fine job of it. That day, though, I was on my hands and knees on a bloody, gory, cold tiled floor, desperately trying to hold those disintegrating bits of life together. Joah was in the warm blood-filled tissues, I knew it, and I had to hold onto him, had at least to find a way not to let him just get flushed down a toilet in an industrialized maw that clearly didn’t care whether he or I lived or died. In the haze and madness of that long afternoon, weak and dizzy and nauseous and in raw, animal-like pain, I understood that this is the norm for women who miscarry in such a place, that I being older at least had some other life experiences to draw upon to get me through (being battered and left for dead, for instance), but what about all the young women, the first-time mothers who have to go through this alone? What about the ones with partners who can’t be bothered? Who helps them? Who picks them up off the floor when they faint? Who locates the blue sheets?

St. Rose of Viterbo Convent, where the Franciscan Sisters of Perpetual Adoration live and pray and work

When it was fully done, I had carefully scraped most of the bloody tissue off that floor and laid it gently in three of those blue plastic pads, folding it over and over, making a packet of my baby to take home with us. We would find a place to bury him, I was determined, and the medical staff was so unavailable they didn’t even notice I’d absconded with what was left of my child. Three days later, emerging from a room at a convent, where we had retreated to come to terms with all this, those remains were still warm, pulsing even. Life doesn’t give up easily. There are things about it that modern science doesn’t know, cannot know, and when we cede our lives to such blinkered visions of reality, we, too, die a little more inside.

When we finally gave him back to the earth he never set foot on, Joah came to me in my dreams. He is a sunny-haired child, with loose curls and blue eyes the spitting image of his father, and a great big smile that is kind and gentle. I was trying to get one of my distant cousins to meet him, saying, “See, here’s our Joah,” but the cousin couldn’t see, no matter how urgently I said it, and as Joah turned to me, placing one hand in mine, I understood at last that the cousin couldn’t see him because Joah was not here for anyone but Stewart and me, and this was how it would ever be. Standing on the bank of the chilly Mississippi later that day, unable to find words for any of it, I wept bitter tears. Usually I do not cry when someone dies. My pattern is to be steely and tear-less for months, sometimes years, and then suddenly to face it all. This time (and every time since), I cried when it hurt. Which was pretty much all the way through.

And I went through my previous days, over and over and over again: did I lift something too heavy? Did I eat something that disagreed? Did that one glass of wine weeks before I’d known I was pregnant do this? There were no answers then, never would be. The nuns prayed for us alongside all the other prayer requests they had. They’d been praying around the clock for 127 years straight, continuing even when the building caught on fire once.

A spiritual director counseled us, offering a gentle piece of advice that, to me, seemed to come in Joah’s voice, telling me that what I had been doing before he arrived—walking dead in a haze of pain that strangled the life out of me and whatever talents I might have every day—wasn’t serving the world or me very well and asking me now to let go and do different. I vowed I would and meant it, the relief palpable, the dreams of Joah more intense. Non-Catholic, I felt bathed in kindness there and hated to leave. But our passage to Paris was already booked, delayed for three days for this loss. A long-planned research trip was to have begun with our anniversary celebration. Instead we spent that burying our only child, and then a couple days later boarded a plane to France. I’d made a promise. I would keep it.

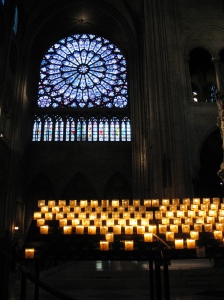

We walked the streets of that old city for days on end, averaging 15 miles per day, traipsing through chilly rain in light coats, practicing our French, wondering how it could be that only two of us were now here to carry on. When we made it to the Notre Dame cathedral, I was stunned at how one place could have carried and held close the hopes, fears, prayers of tens of thousands of human beings. We stood in the crowd of supplicants and lit a candle for our Joah, leaving it to burn itself out alongside hundreds more. Then we went back to our room and I finished the blanket I was knitting for him, not knowing now what child it could comfort.

The next day we stumbled onto the small chapel of Ste. Clothilde, its tiny garden bursting with flowers and hope and all things good. In the lee of its nave, I felt safe, assured of a place somewhere in this world. With no promises of anything after, we humans must simply make do. I promised my little boy that I would wake up from my sleep and do the thing I was put here to do. One part of that? No matter what the cost, I will raise my voice and pen against the Ills of Now whenever they arise and I have some standing from which to speak.

So now we have corporations seeking to block employee access to safe, insurance-covered contraceptives in the name of their “religious values,” which will make it harder for many women to plan their childbearing years and provide the best space and timing for their children. We have states seeking to make miscarriages “investigational events,” ensuring that women like me will be treated like criminals at one of the most painful times of their lives. If these efforts succeed, the police and judges will get to decide whether or not the woman is guilty of a crime, even though modern medical science can’t tell us jack siccum about what causes most miscarriages (some, but not most). Someone like me could go to jail even though I was doing everything in my power to keep my baby well and alive, to carry him to term, to raise him to adulthood. Someone not like me—young, not white, poor, possibly struggling with addictions that are believed to harm children in the womb? Someone like Rennie Gibbs in Mississippi? She will be far more likely to be punished for losing a child. That’s the reality of such laws. Whether alone or with a loving partner, women will suffer. Fathers will suffer. Families who were hoping for these children to join them will suffer. That‘s the reality.

Here’s the thing. Corporations and judges and churches and the police and our neighbors aren’t fit to rule on such matters; even god hides all faces in the face of such terrible dealings as our bodies hand out to women on ordinary days—and that’s without counting having to reckon with and endure the uninformed and meanhearted and uber-big-governmented shock troops who spend all their time and energies on the highly abstracted ‘unborn’ with no clue whatsoever about what it means to give birth to an actual child (much less raise one in less than optimal conditions). They think that big government and militarized domestic police forces should force women not to miscarry, and that women like me who do should be treated like criminals: presumed guilty until proven innocent, despite the fact that for such matters no proof could ever suffice. I am no feminist—never have been and do not intend to start now—but where these things are concerned, I’m all steely will that This Shall Not Come To Pass With My Consent. I will resist to the last cell of my being. Nor will I stay silent, lest someone take offense. (Taking offense is how this society now keeps too many decent people in line. So many citizens are scuttling along, trying to stay out of the line of fire: if I say x, my boss may take offense, etcetera, so I’ll just keep quiet. It is a crying shame.)

I have lived sorrows bittersweet enough for all tomorrows ever rolling in: I will not remain silent while such ugly shortsightedness strides so hard on the jugulars of my half of this species. This Meanness Shall Not Prevail. We are simply not this ignorant any longer. We are not.

I lit a candle at Notre Dame for my son. He had to leave before he ever got here, but I promised him that I would participate in my world for as long as I am in it, that I would do my best to make it a kinder place more worthy of him and his peers, that I would not unplug to avoid unpleasantness again, that I would not allow the callous to take over with no resistance from me, his mother. On this I stake my all. We must somehow find it in our hearts to meet these Ills of Now, these ions, these steady attempts at inculcating societal meanness as our daily norm, and we must meet them with dignity, steely resolve, and actions. I will do this taking one more cue from our Joah: I will smile on the way. Big, sincere smiles, for one and all. I lack his sunny curls and blue eyes, but I will smile and mean it. I will boycott, protest, resist, sign petitions, vote for non-knuckleheads, spend my money with businesses that do better and avoid those that don’t, speak up and tell others and join in their efforts, too, my yes, but I will smile and I will mean it: Meanness Shall Not Prevail Among Us. Our children deserve better. As do we, their oh so flawed but worthy older peers.