This morning a friend shared an article by Elizabeth Segran about people who earn PhD degrees, but then cannot find work in their chosen fields. I was struck by the wise, calm observations: how does one find meaning on leaving the place one expected to serve as a lifetime home? Academia, of course, is presently exploitative, shedding tenure-track jobs like lice leaving a kerosene-soaked head; most of the people who are earning PhDs will never obtain positions there (or will do so only as one of the underpaid adjuncts required to keep the unsustainable struts of the system above water); tuition and enrollment and grade inflation keep climbing, as do massive investments in the administrative and customer-service and college-sports sides of the industry alongside deep cuts for non-tenured faculty and teaching in general; whole disciplines are being axed or reduced to shambles; and the situation is in such a steep all-out freefall at present that it is hard to imagine what the university system will be in a decade or two.

My personal response to all this has been as much about grieving the loss of scholarly and learning traditions that I value as it is about the time, effort, and money I personally have expended to get a worthless credential and advanced skills that are no longer widely valued and thus cannot easily be turned to making a contribution. The grieving and the leaving, however, make way for a clearer-eyed perspective on not just academia, but life.

Segran gazed calmly at the state of things in her field and higher ed and, degree in hand, chose to leave for an entry-level position in a PR firm. She writes:

It is true that I do not feel the same obstinate devotion to my PR job that I once felt about academe, but perhaps that is a good thing: The fact that I am not wedded to my job means that my employer does not have the power to exploit me in ways that universities exploit their workers. Also, while people everywhere fuse their personal identity with their work, that tendency is much more pronounced inside of the academy than outside it. In my new life, I can leave my work at the office and pursue my other passions in my free time, an arrangement that gives my life more flexibility and balance.

Obstinate devotion: such a perilous milieu: in its maw and intermittently unaware, as happens to many of us in graduate school? It is so easy to sell out your whole life for a goal that was never possible anyway. Unlike Segran, I am free now to do precisely what I love—writing books and stories as I’ve done for years, continuing with memoir and fiction and moving now toward tackling historical subjects for general audiences (as both nonfiction and novels). I’m fortunate, too, to be able still to teach—as an online adjunct for a state university—and thus get the chance to hone my skills in teaching history as one of the ‘lively arts’, a living breathing practice that is not (and should not be) confined to the ivory tower nor dispensed solely by talking heads on documentaries or op-eds.

With the security of a tenure-track position, wage, and benefits, some of this could have been easier, perhaps. But given traditional academic disciplinary norms for publication, my writing would likely never have fit in. It is not insignificant here that when I published my first book, a memoir in 1997, I was warned both by professors and fellow graduate students that publication in such a “popular genre” would hurt me in the search for a tenure-track position. I would not appear, apparently, to be serious about scholarship. So be, I thought, imbued with my obstinate devotion to my fields (early US history and ethnography) and to preparing for my career—which I funded with a full-time night job, part-time teaching and on-campus positions, grants, and student loans—and went right on with both memoir and fiction, deepening my engagement with primary sources and beginning to work out an ethnographic approach to the archives and places I studied. I was sure that I could develop skills enough to counter such notions, to possibly even demonstrate that engagement with the public in different genres could be a valuable addition to the academic stables. When I won a campus-wide award for excellence in undergraduate teaching, my heart fairly sang because this meant I had a chance and maybe all their notions could be wrong-headed after all and I would one day have a home in the world (always one of the key perks of academia for me). But no, I was the wrong-headed one, off by leagues and fathoms uncountable!

For a year after completing my degree, I hit the wall of the academic job market with sustained will, facing the realities of this field: funding for research and conference travel is limited and those of us with the least ability to pay are the ones most likely to have to self-fund. Although fortunate to land an adjunct position in a department and university that values its part-time employees enough to provide benefits and true collegiality, there’s no job security (no matter how great a job I do!) and the pay isn’t sufficient to fund research or conference-going. Happy to connect with students, I scaled down my research plans and fired up two non-academic writing projects that had lain fallow due to both work and trauma, and—still cultivating a profoundly obstinate devotion to the craft—I continued working on a couple of academic journal articles as well. The latter made limited sense, because I believed their insights were valuable to my sub-fields since no one has made them before; and I figured that submitting them for publication might increase my job chances.

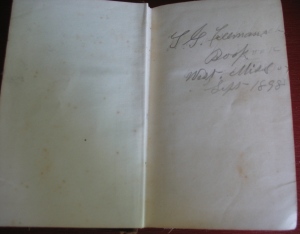

Then one day, abruptly and thanks solely to my students—many of whom will never take another history course or have access to university library resources to study history in their free time once they graduate—and to my grandparents (neither of whom went to college, but still bequeathed me their stories and histories and the small book pictured here), I woke up to my own obstinate devotion and understood at last how cockeyed it was. Why would someone like me who is not on a tenure track willingly publish behind a pay wall that most people can’t access? An article in the Journal of American History or Gender & History isn’t easy for a person on the street to access; most of them are geared for a tiny specialist audience at best; maybe some will shift the discipline(s) significantly enough to show up as required readings for students at some level, but maybe not: these writings serve the disciplines and people whose careers are in them. They serve the tenured and the tenure-tracked, a very few of whom may serve as talking heads or op-ed writers and thus reach a wider audience, but what about the histories that all the rest of us live and make every day? That single question—on the heels of nearly a quarter-century of my quest to be qualified to practice ethnographic history—led me to rethink my relationship to the academy, to my disciplines, to my writing, and to my career. I am far too serious about my writing to take on another full-time job to make up for the wage grade of adjuncting, as Elizabeth Segran did**; and I still love the give-and-take of teaching so much that I can’t turn down an opportunity to do it either: yet I, too, have come to a place of calm observation.

Now I view history as one of the ‘lively arts’—something we inhabit as minnows do water, something we take in through our gills every day without conscious effort or thought, something that embodies us before we are even born and outlasts us even after we die. Writing, too, is another of these ‘lively arts’, as is performance in any genre, but history is a great deep well of humanity that never ceases to slake my thirst for connecting in some small way with those who came before, those who will come long after us, and we who are here now (so often bereft of comfort, for we know not of our connections). I work daily to revitalize how I teach so that students can feel this liveliest of arts in their bones, inhale the stories and the worries and the struggles and the wonders of long-past times and peoples, and then come up able to dance and story and sail across the turbulent waves of being, with the fires of shared and unshared histories bright about them, no matter what careers they choose: so that they glimpse themselves not simply as people now, but as historical characters in the making, dwelling fully in not just this but all places and times. My days now are more sane and less capricious, and they turn on practical and philosophical questions that were valuable to me as an undergraduate and citizen and human being, which is a more capacious field of endeavor than are the more narrow lines of inquiry allowed to those who pursue advanced degrees for the purpose of finding employment in the formal academy. My questions for history and teaching are about usefulness and the in-spiriting of this work in the world.

How can I find sources and resources that will lure students in and whet their curiosity enough that they’ll want to track through the evidence with me or alone? How can I dismantle the read/regurgitate-on-test models so common to history education in the U.S. without frightening students accustomed only to those or wearing myself to a nubbin? (The student-to-teacher ratio at state universities inveighs hard against creativity in teaching, primarily because of the time and wage factors for adjuncts, but I’m finding a few tactics that seem to work.) How can I open up the ways in which students can demonstrate their increasing skills without forcing them all into the trusted modes that served the last century okay, but no longer suffice (heavy on written analysis, often timed on exams or for ‘research papers’)? How can I find the time to locate the best web and e-tools for enhancing learning and curiosity, while steering clear of those that deaden both? How can I give them tools that will help them challenge pundits and talking heads and ‘experts’ (even myself) alike? How can I create a non-hierarchical, collaborative learning environment that lets students have more control than they may be accustomed to having?

How can I use my writing and my understanding of how one story gets smithed into a play or a feature film or inspires a song to hear better the genres in which my students may wish to approach history proper? How can I help them to discover that history is personal, about not just ‘them’ but us, about not just back then but now, and thus deserves close scrutiny (far more than is required for any exam)? How, most of all, can I give them a truly high-quality experience that mirrors the best courses of my undergraduate years at the Claremont Colleges—so that wealth and social position play no role whatsoever in the quality of their coursework? For that is, indeed, the thing about the present freefall of academia that I grieve—even lament—the most anymore: education when industrialized may turn out workers, but to do so it has to service a privileged set and exploit others while denying that set of tactics pretty determinedly and systematically in practice, and so it drastically deepens inequalities and thus harms society across every last board. Changes are needed, my yes: transformation is needed, for these systems have been increasingly out of kilter for at least the last 20 years. I saw that firsthand while in graduate school and painstakingly (and at great expense!) prepared myself to work within the system to help change it. Now I’m outside and thus cannot do this, and grieving too long is a waste of my time on this planet. Obstinate devotion, however, is a worthy trait, and I intend to haul it aboard and re-bore its lenses and hone it in myself for good.

I’m focusing on smaller goals now, none of which offer me any institutional succor or welcome: becoming a better writer with each page, each sentence, each word, each comma and dash; studying my characters with the deep gaze of the ethnographer and library sailor and finding the perfect voice for each project; staying wide-open to the challenges of different genres, but gradually putting more of my ethnographic and historical passions into all of these stories; becoming a better, more compassionate teacher with each course, each week, each assignment, each response; becoming more open to the real diversity of my own personal history, my training, skills, and contributions, as well as that of my students; taking the time to volunteer and engage with my local communities and neighbors (both human and not); setting ‘work’ aside for some part of every day to rest and regroup or simply read or sew or knit or quilt or play music or tramp outside for the sheer fun of it. In short, I am dwelling fully in it all, rowing my little boat steadily into the standing waves of these lively arts I have been so fortunate to journey in while here. Every last jot of the lot is relevant to every other one; none stands apart, at loose ends: the waves are formed of droplets of singular energy both small and mighty yet immersed in the whole, and not the tiniest thing—not even a glance or a sigh—goes amiss. All that is or ever was rides alongside, noticed or not, reachable or not, and swells the seas of existence in which I—and all that ever was or will be—dwell.

I am, I see now, thoroughly well-companioned, though I often did not see this before. Whatever comes later? Comes. I am already at home in the world. How do I know? This little book (pictured above, inscribed in pencil by my mother’s father’s father as his “Book” in Sept. 1898), only recently found and yet to offer up any of its or his secrets or stories? For which I will need to plumb old newspapers and letters and archives; fire up my microfilm and micro-opaque readers; and most surely travel to “West, Miss.” for the first time ever (since this is how I do ‘history’)? Tells me it is so.

**I made an error in the sentence structure which suggests that Segran also pursued adjunct teaching alongside her PR job: this is incorrect.

~